Your Read is on the Way

Every Story Matters

Every Story Matters

The Hydropower Boom in Africa: A Green Energy Revolution Africa is tapping into its immense hydropower potential, ushering in an era of renewable energy. With monumental projects like Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the Inga Dams in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the continent is gearing up to address its energy demands sustainably while driving economic growth.

Northern Kenya is a region rich in resources, cultural diversity, and strategic trade potential, yet it remains underutilized in the national development agenda.

Can AI Help cure HIV AIDS in 2025

Why Ruiru is Almost Dominating Thika in 2025

Mathare Exposed! Discover Mathare-Nairobi through an immersive ground and aerial Tour- HD

Bullet Bras Evolution || Where did Bullet Bras go to?

The torrents that have pounded Nairobi over the past few months haven’t just disrupted commutes or flooded neighborhoods—they’ve laid bare the city’s fragile infrastructure and deeper political fractures. Governor Johnson Sakaja may present himself as a pragmatic leader trying to fix a broken system, but the ongoing deluge has revealed a more complex story. One where engineering failure meets fiscal strangulation, and where political turf wars threaten to sink the capital even deeper into crisis.

Nairobi’s drainage system is not just outdated—it’s obsolete. Designed in an era when climate patterns were more forgiving and rainfall predictable, the city’s stormwater channels were built for occasional seasonal showers, not the modern-day tropical torrents driven by climate change. The result? Overwhelmed drainage lines, flooded roads, and knee-deep water in neighborhoods that have become virtual swamps. Governor Sakaja, in recent interviews, has acknowledged the inadequacy of the existing infrastructure. However, he insists the real enemy is a lack of resources and cooperation from the national government. While Nairobi’s county engineers and cleanup crews do their best with what they have, the problem is simply too large for patchwork solutions and stop-gap measures.

The county’s most visible response—a 3,800-member “Green Army” made up of youth tasked with garbage removal and drain clearance—is both commendable and tragic. Commendable because it reflects an effort to engage the community in cleaning up their environment. Tragic because no amount of manpower can solve structural problems that run meters below the surface and decades into the past. The Green Army has become the face of a city trying to bail out a sinking boat with a teacup.

In Parklands, one of Nairobi’s more flood-prone neighborhoods, a glaring symbol of poor coordination between government agencies stands tall—and soggy. Ojijo Road, a key route in the area, features a drainage outlet that inexplicably narrows from 1.2 meters to just 0.6 meters. This design flaw, according to Sakaja, was the work of the Kenya National Highways Authority (KeNHA) during the expansion of Thika Road. Predictably, this constriction has led to a consistent backup of rainwater, turning the road into a seasonal riverbed. While Governor Sakaja claims to have pushed KeNHA to correct the problem, and they’ve made partial improvements on Kipande Road, the broader pattern persists: piecemeal fixes, institutional blame games, and zero accountability.

These types of engineering mismatches raise uncomfortable questions. Was it mere incompetence that allowed such a blatant flaw? Or is there a more systemic issue of poor planning, hasty project execution, and lack of consultation between national and county-level stakeholders? Whatever the case, it’s Nairobi’s residents who pay the price in soggy shoes, stalled cars, and rising public health risks.

Looming large over Nairobi’s flooding saga is a deeper fiscal conflict—the battle for the Road Maintenance Levy Fund (RMLF). Every Kenyan pays into this fund with every fuel purchase, but its disbursement is tightly controlled by the national government. Counties, which maintain over 65% of the country’s road network, see only a fraction of these funds, if any at all. According to Sakaja, this imbalance is a major reason why city infrastructure continues to deteriorate. Without access to the Ksh.10.5 billion currently frozen due to court disputes, counties like Nairobi are essentially being asked to perform major surgeries with pocket change and garden tools.

The situation has turned into a political flashpoint. While county governments argue for greater fiscal autonomy, the central government remains unwilling to relinquish control. This tug-of-war is not just bureaucratic—it has real, devastating consequences for millions of people. Roads remain unrepaired, drainage channels are never upgraded, and emergency response systems are overstretched every time the skies open up.

President William Ruto has recently waded into the debate, not with an olive branch but a proposition: give him full authority over the disbursement of RMLF funds, and he promises better planning, faster projects, and nation-wide improvements. On the surface, it sounds reasonable. Centralized oversight, after all, could bring consistency and efficiency. But critics see it differently. For them, Ruto’s proposal is yet another example of power consolidation disguised as reform. By holding the purse strings, the national government effectively strips counties of the very tools they need to be self-reliant.

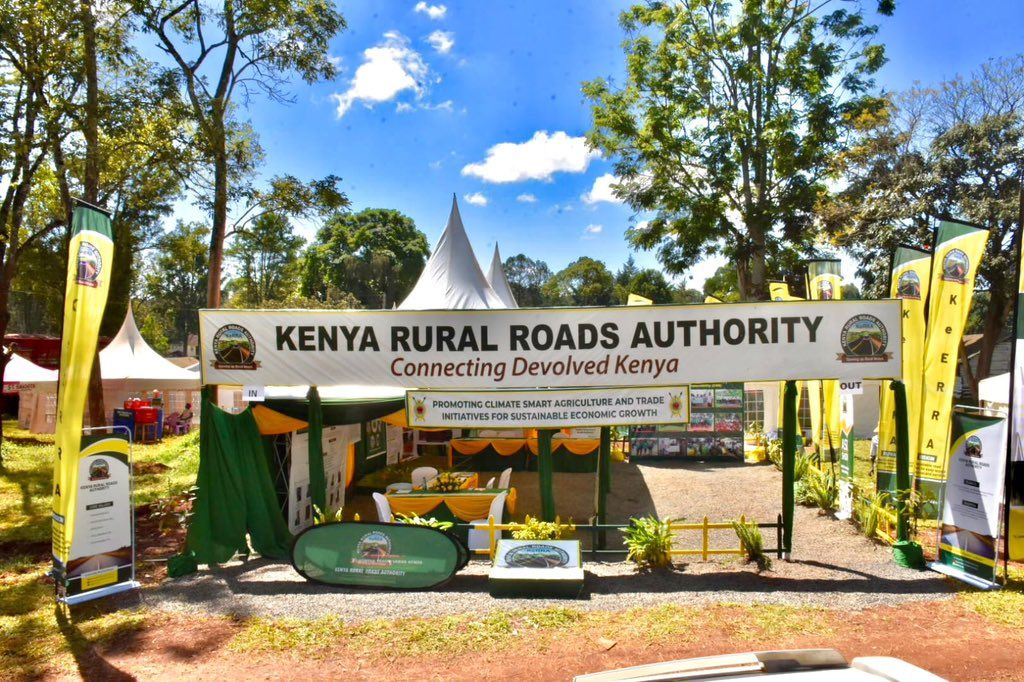

Former Prime Minister Raila Odinga has added his voice to the fray, calling for a total overhaul of national road agencies like the Kenya Rural Roads Authority (KeRRA). These bodies, he argues, should be operating under county jurisdictions—not making decisions from offices in Nairobi’s Central Business District. Governor Sakaja echoed this sentiment, rhetorically asking why rural infrastructure authorities are involved in urban planning. It's a legitimate concern that underscores how jurisdictional confusion continues to mire development efforts in endless red tape.

Ultimately, the story of Nairobi’s flooding isn’t just about weather, drains, or poor road design—it’s about governance. It’s about two layers of government that seem more interested in blaming each other than fixing the problems. It’s about a capital city that is rapidly modernizing above ground while rotting below it. And it’s about the ordinary citizens—commuters, traders, schoolchildren—who are forced to navigate a broken system with no lifeline in sight.

Until there’s a fundamental shift in how infrastructure is funded, designed, and managed in Nairobi, the city will remain trapped in a vicious cycle. A downpour becomes a crisis, a crisis becomes a headline, and a headline becomes another political opportunity—until the waters rise again.

0 comments