Your Read is on the Way

Every Story Matters

Every Story Matters

The Hydropower Boom in Africa: A Green Energy Revolution Africa is tapping into its immense hydropower potential, ushering in an era of renewable energy. With monumental projects like Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the Inga Dams in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the continent is gearing up to address its energy demands sustainably while driving economic growth.

Northern Kenya is a region rich in resources, cultural diversity, and strategic trade potential, yet it remains underutilized in the national development agenda.

Can AI Help cure HIV AIDS in 2025

Why Ruiru is Almost Dominating Thika in 2025

Mathare Exposed! Discover Mathare-Nairobi through an immersive ground and aerial Tour- HD

Bullet Bras Evolution || Where did Bullet Bras go to?

The Constitution of Kenya, 2010, boldly anchors the rights of persons living with disabilities (PLWDs) in law, offering them constitutional recognition and protections. Article 54 establishes the state's duty to ensure inclusion in education, employment, public life, and access to facilities. Yet, despite this progressive legal foundation, implementation has lagged dramatically behind.

Over a decade later, the majority of PLWDs in Kenya still face daily barriers that deny them the dignity and opportunity that the Constitution promises. This disconnect between legal rights and lived reality paints a troubling picture of selective governance—one where those most in need of state protection remain invisible in the corridors of power.

Kenya’s legislative landscape is not short of disability-focused policies and acts. The Persons with Disabilities Act, enacted in 2003, was one of the continent’s earliest attempts to institutionalize disability rights. However, as with many other statutes, its impact was dulled by poor enforcement, underfunding, and a lack of structured oversight.

In 2022, a Parliamentary Committee audit starkly illustrated the problem: public institutions had consistently failed to meet the required 5% employment threshold for PLWDs. Human resource frameworks remained rigid, unaccommodating, and outdated. This trend of inertia underscores a pattern where legislative intention is routinely undermined by bureaucratic apathy, inadequate political will, and insufficient regulatory teeth.

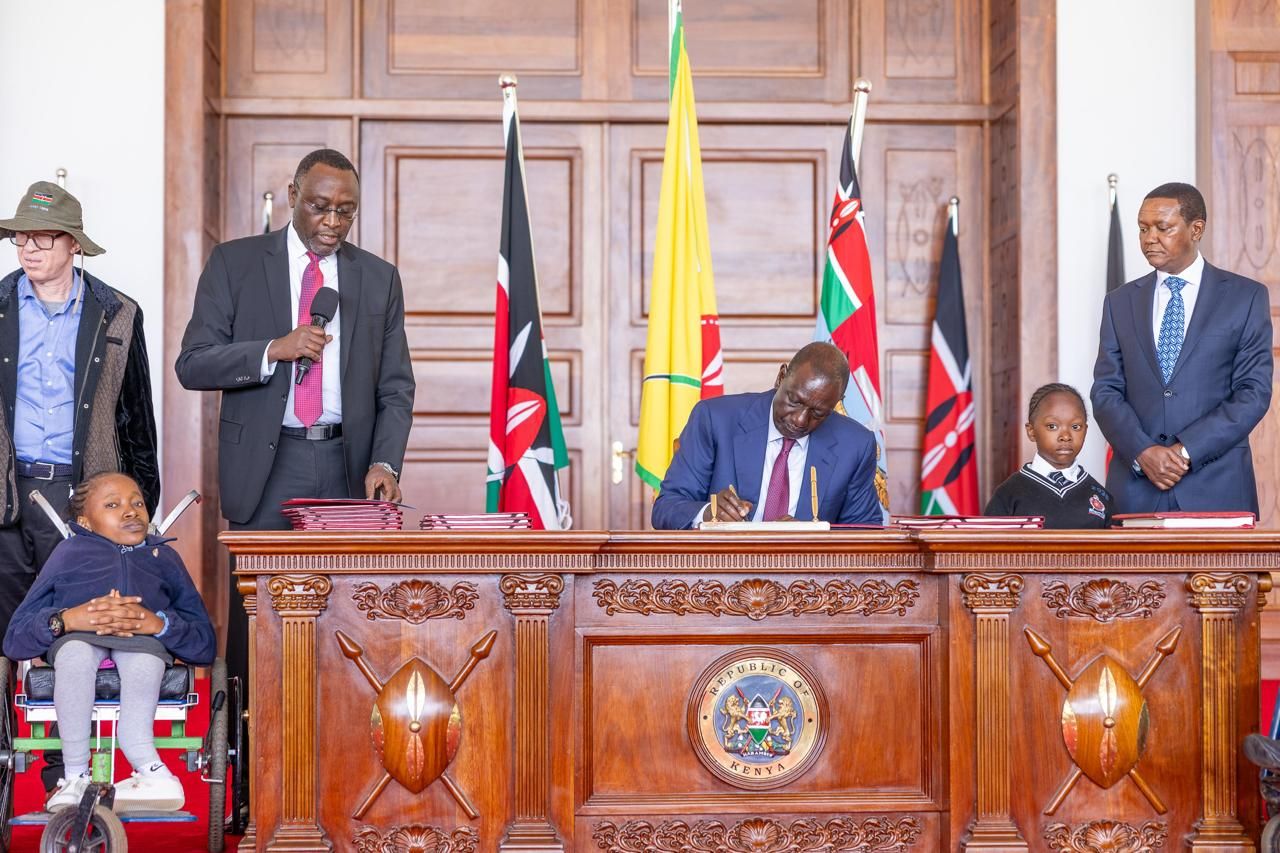

With the recent assenting of the Persons Living with Disabilities Act, 2025, President William Ruto’s administration has signaled a desire to reset the clock on decades of exclusion. The new law outlines a robust framework for the inclusion of PLWDs, mandating their representation in policymaking processes, introducing quotas in employment, and offering guidelines for accessibility in public institutions.

It sets forth ambitious targets that, if faithfully implemented, could redefine Kenya’s social contract with its disabled citizens. However, as with previous attempts, skepticism lingers. Will the law catalyze real, on-the-ground transformation, or will it follow the path of its predecessors—strong on rhetoric but weak on results?

The passage of legislation is only the beginning. Without firm structures to monitor, evaluate, and enforce the provisions of the 2025 Act, the law risks becoming another symbolic gesture. Implementation must be systematic and deliberate, with regulatory timelines and consequences for non-compliance.

The National Council for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) must be empowered to operate independently, with the authority to audit public and private institutions, hold them accountable, and ensure real-time data collection on disability inclusion. Proper training of civil servants, especially at county levels, must accompany these enforcement mechanisms, alongside increased budgetary allocations to facilitate accessibility in infrastructure and services.

Kenya does not need to reinvent the wheel. Nations like Sweden, South Africa, and Canada have established strong inclusion systems that integrate PLWDs across all sectors of society. These countries have embedded disability rights into urban planning, education, public service, and digital infrastructure.

Kenya can learn from these global models, particularly the emphasis on intersectionality, inclusive technology, and universal design. Adopting global best practices is not merely about emulation—it is about contextual adaptation. For Kenya to transform into an inclusive society, policies must reflect not just international aspirations, but local realities and community voices.

Perhaps the most stubborn barrier to disability inclusion in Kenya is not policy-related—it is cultural. Deep-seated beliefs continue to frame disability as a curse, a punishment, or a divine anomaly. These myths have devastating consequences: children with disabilities are hidden from public view, denied schooling, and subjected to lives of isolation. The new law must be accompanied by a national campaign to dismantle these prejudices.

Civic education, storytelling, inclusive curricula, and media representation must play a leading role in reshaping public perception. True inclusion cannot exist alongside stigma; both cannot breathe the same air.

The true test of the 2025 Act will not lie in Nairobi’s polished press conferences, but in the dusty roads of rural Kenya. County governments must localize national policies and empower communities to become part of the inclusion conversation. Village elders, community health volunteers, local NGOs, and school heads must all be brought into the fold. Grassroots structures can become powerful agents of change if they are equipped with information, resources, and the mandate to lead locally-owned inclusion initiatives. Only when the law is felt and understood at the community level will it truly take root.

Independent oversight bodies, particularly the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC), play a crucial role in holding systems accountable. These institutions must be insulated from political interference and given the freedom to conduct audits, recommend sanctions, and guide public institutions in implementing disability-friendly practices. Their reports should inform budgetary decisions, shape policy revisions, and direct national conversations. Oversight must not be performative—it must be loud, authoritative, and unafraid to expose inefficiencies or resistance to change.

Kenya has taken a bold step with the 2025 Disability Act, but the road ahead demands more than well-written legislation. It requires moral courage, financial commitment, and a collective national will to reimagine the country as a place where no citizen is left behind. The time has come to move beyond promises and public relations. What PLWDs need are not more speeches—but equal opportunities, dignity, and full citizenship. Anything less would be a betrayal of the Constitution’s vision of a just and inclusive Kenya.

0 comments