Your Read is on the Way

Every Story Matters

Every Story Matters

The Hydropower Boom in Africa: A Green Energy Revolution Africa is tapping into its immense hydropower potential, ushering in an era of renewable energy. With monumental projects like Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the Inga Dams in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the continent is gearing up to address its energy demands sustainably while driving economic growth.

Northern Kenya is a region rich in resources, cultural diversity, and strategic trade potential, yet it remains underutilized in the national development agenda.

Can AI Help cure HIV AIDS in 2025

Why Ruiru is Almost Dominating Thika in 2025

Mathare Exposed! Discover Mathare-Nairobi through an immersive ground and aerial Tour- HD

Bullet Bras Evolution || Where did Bullet Bras go to?

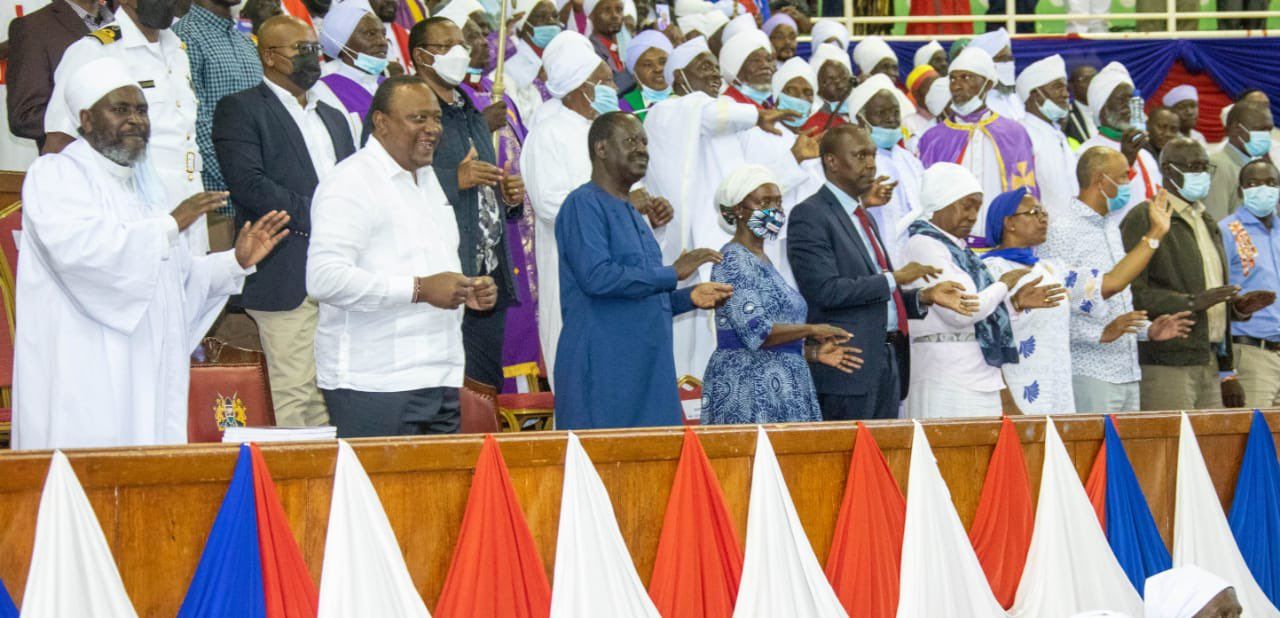

In Kenya’s spiritual landscape, the Akurinu remain one of the most misunderstood yet resilient religious groups. Easily recognizable by their signature white turbans and robes, this indigenous Christian denomination emerged in the 1920s—during the colonial era—as a distinctly African spiritual response to foreign domination, cultural erasure, and imposed Christianity. They did not just adopt a faith; they redefined it, anchoring it in African prophecy, dreams, and community healing.

Their full name—Holy Ghost Church of East Africa—barely scratches the surface of a movement that combines Christianity, African spirituality, and prophetic traditions into a deeply communal way of life. Their practices often baffle outsiders, but to the Akurinu, obedience to God, modesty, and spiritual clarity are paramount.

The Akurinu faith wasn't born in churches or seminaries—it was born in dreams and visions. In the early 20th century, colonial missionaries had reshaped indigenous beliefs, attempting to subdue African spirituality. The Akurinu emerged as a spiritual uprising, led by prophets and visionaries who claimed divine messages urging them to reject European cultural influence and instead pursue a purified, spirit-led form of Christianity.

Their founders—mostly ordinary farmers and laborers—reportedly received heavenly visions calling for repentance, white garments, and a return to spiritual obedience. They rejected Westernized worship formats, music styles, and hierarchical clergy, insisting instead on direct, unmediated relationships with God. The turban was more than attire; it was a shield, a declaration of separation from colonial contamination.

Worship in an Akurinu church is unlike anything seen in mainstream Christianity. Services are filled with chanting, dancing, drumming, and prayerful trances. Silence often falls when a prophet among them rises to speak—interpreting dreams, issuing divine warnings, or guiding community choices.

They believe in the tangible presence of the Holy Spirit during services, often expressed through spiritual tongues, trembling, and weeping. Dreams are sacred, and many decisions—personal and communal—are based on dream interpretations. Healing and exorcism are also central, conducted by spiritually gifted individuals believed to carry divine authority.

For many Kenyans, the Akurinu’s dress code remains their most distinguishing (and sometimes divisive) feature. Men and women wear long, loose-fitting white garments and keep their heads covered at all times. The turban is not only spiritual armor—it is symbolic obedience to God’s command as delivered through dreams to the early prophets.

Yet this distinct appearance has led to widespread stigma. Akurinu children are often bullied in schools, and many adults face discrimination in workplaces or social settings. Still, members of the faith rarely abandon their dress codes. To do so would be, in their view, to abandon their covenant with God.

In recent years, a new generation of Akurinu youth has begun reclaiming their narrative—using social media to celebrate their identity and challenge stereotypes. Many are educated, politically active, and fashionably blending modernity with faith, all while upholding their deep spiritual roots. Gospel musicians from the Akurinu faith now perform on national stages, and influential figures in business and politics proudly represent the community.

Despite this visibility, internal challenges persist. The Akurinu struggle with leadership disputes, generational rifts, and pressures to “modernize” their doctrine. But even amid these shifts, their core mission remains: obedience to God, preservation of prophetic traditions, and healing a spiritually broken world.

The Akurinu are not just a religious group; they are a spiritual counterculture. They remind us that Christianity in Africa didn’t just arrive by ship—it was reinterpreted, resisted, and reclaimed. In a world racing toward conformity, the Akurinu stand still, grounded in revelation, resisting the noise with silence and prayer.

0 comments